Viktor Filinkov, political prisoner: “An idealist who takes on responsibility for the big picture”

People and Nature

July 4, 2020

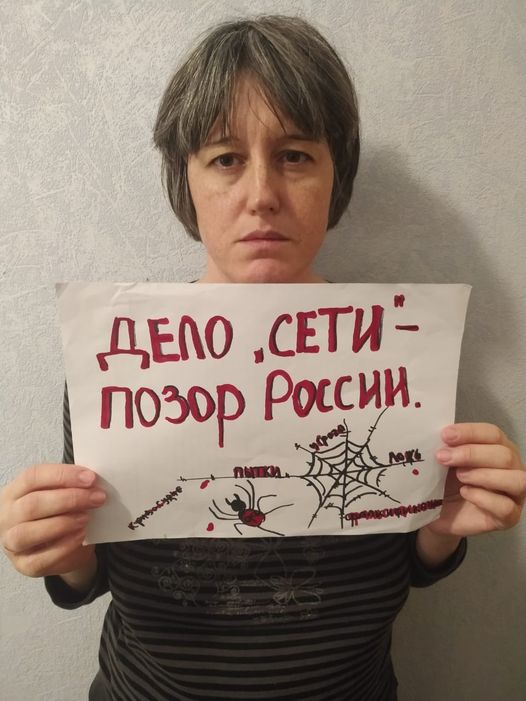

While Black Lives Matter demonstrators fill the streets of cities around the world, opening a new chapter in the history of anti-racist and anti-fascist struggle, the Russian anti-fascists Viktor Filinkov and Yuli Boyarshinov are starting long jail sentences.

A St Petersburg court sentenced Filinkov to seven years, and Boyarshinov to five-and-a-half, on 22 June, on trumped-up charges of involvement in a “terrorist grouping” – the “Network”. In February, seven other defendants were jailed by a court in Penza for between six and 18 years, and last year another in St Petersburg for three-and-a-half years.

Detailed evidence that the “Network” case defendants were subjected to horrific tortures after their arrest has been published and submitted to state bodies. President Vladimir Putin last year cynically promised to look into it. Nevertheless, the defendants have been railroaded to penal colonies.

This portrait of Viktor Filinkov – who refused to admit guilt and received one of the heaviest sentences – is by Yevgeny Antonov. It was first published in Russian by the Petersburg news outlet Bumaga.

Viktor Filinkov in court. Photo by David Frenkel, Mediazona

On Monday 22 June, the 2nd Western District Military Court [in St Petersburg] announced the sentences on the Petersburg defendants in the “Network” case, Viktor Filinkov and Yuli Boyarshinov. They were found guilty of involvement in a terrorist grouping (article 205.4, part 2 of the criminal code). Filinkov was sentenced to seven years in a penal colony (standard regime). Boyarshinov got five and a half years (Yuli was also convicted of the illegal possession of explosive materials (article 222.1, part 1)).

Four days before the sentencing, Filinkov addressed the court. The 25-year old computer programmer set out the inconsistencies in the prosecutor’s case, and used diagrams to show why the PGP [Pretty Good Privacy encryption] programme would not be used by a conspiratorial terrorist group, as the prosecution had claimed.

In his closing statement, Filinkov stated that the internal affairs ministry, the prosecutor, the federal prison service, the Investigative Committee, the federal security service [FSB], the court and the legislature had worked in bad faith. He accused them of obeying orders unquestioningly and of being unwilling to investigate the case.

“The nine-year sentence that the prosecutor has asked for seems like some sort of indication of respect for everything that I have done”, Filinkov said. “All of them have disgraced themselves. I don’t know what the solution to this situation is.”

Viktor Filinkov at work. Photo courtesy of Rupression

Viktor Filinkov at work. Photo courtesy of Rupression

Viktor Filinkov was born in Petropavlovsk, in Kazakhstan. His mother worked in a jeweller’s shop; his father, who worked installing medical equipment, died when Viktor was 11; and his elder sister lived away from home.

“We waited so long for Viktor. And when he was born, he grew up loved and cared for, by grandparents, by his aunts and uncles, and by us”, Natalia Filinkova, Viktor’s mother, told Bumaga. “He hardly knew the word ‘no’. He was a good, kind child, very honest, strong-willed. Right from when he went to nursery, if he didn’t like something, he would say so straight out. He would tell anyone, to their face, what he thought. I used to ask him, ‘why so direct?’ and he would answer ‘because it’s true!’.”

According to Natalia, electronics caught her son’s imagination when he was still a child. At six, he used his sister’s computer to read up about it. At ten, he would put together robots. As a teenager, he learned programming and won computer competitions. In court, Filinkov’s colleagues from the IT company where he worked confirmed his remarkable skills as a programmer.

“He hadn’t yet started going to school, when he told me, when I grow up I’ll be professor, earn lots and lots of money and buy KAMAZ [the truck construction company], so that it can make lots of money too. He obviously thought professors are high earners”, Natalia joked.

After Viktor’s father’s death, the family had to spend less, and moved to a smaller flat, but was still free of serious financial problems. Viktor’s wife, Aleksandra Aksenova, said that he described his childhood as difficult. “He saw how his mum and his sister kept their noses to the grindstone. But still, they had no money for meal time treats. I well remember how Viktor said that, when he was a child, butter was a real treat. It was not starvation, but it was definitely poverty.”

Viktor is described as a sociable person, with dozens of friends, who loves social gatherings. According to his mother, he was a voracious reader as a teenager – of technical books from school in particular. And he would sit on the internet and play computer games.

Aleksandra Aksenova says that Viktor mentioned to her his dislike of the education system in Kazakhstan, and his frequent arguments with his school teachers. “One thing that’s striking about Viktor is that he loves a good argument. Once he has worked out his position, he is very good at defending it. But also, if it turns out he is wrong, he’s not afraid to say so.

“Although he didn’t like the way the school system worked, he was anything but stupid. With STEM subjects he was in his element. And he argued with his teachers, often because he knew more than they did.”

Viktor himself says that, as he got older, he wore his hair long, on account of which the school management “tried to put pressure on him”. Around this time, Filinkov’s anti-fascist and anarchist views took shape.

Viktor Filinkov (third from left) with schoolmates in Kazakhstan. Photo courtesy of Mediazona

Viktor Filinkov (third from left) with schoolmates in Kazakhstan. Photo courtesy of Mediazona

“At some point when Vitya was in the 9th year [i.e. at 15], he said that he had become keen on anarchism”, Natalia Filinkova remembers. “Surely he read about it on the internet, there was plenty

Viktor Filinkov (third from left) as a school pupil. Photo: zona.media

written there. This was shortly after [the lawyer, Stanislav] Markelov and [the journalist Anastasia] Baburova were killed [in Moscow]. This had a real effect on Viktor; he wanted justice.”

Viktor’s mother says, however, that they did not talk about politics. In court, she said: “He was a good example to others. At no time did he suggest that he was against the government.”

Viktor Filinkov in happier times. Photo courtesy of Rupression

Viktor Filinkov in happier times. Photo courtesy of Rupression

In 2013 Viktor finished school and moved to Omsk, [in western Siberia, in Russia] where he started studying in the faculty of information and communications technology at Omsk state university.

Viktor never graduated. After two-and-a-half years he abandoned his studies, because his mum became “seriously ill”. (Natalia asked that the diagnosis remain confidential). Filinkov started work, earning 30,000 rubles [400 euros at 2016 exchange rate] per month.

Viktor was happy to quit university, a friend from that time told Bumaga; he complained that classes were boring. This source said that Filinkov soon understood that he had hit the pay ceiling in Omsk, and thought about moving on.

Viktor’s wife recalls that at that time he began to participate in anti-fascist actions and to support human rights campaigns. In 2014-16 he stood on picket lines opposing redundancies among health workers, supported trade unions and attended demonstrations in memory of Markelov and Baburova.

By 2015 Viktor was a committed anti-fascist, an acquaintance from Omsk told Bumaga. According to them, Viktor came to these beliefs himself, without reading “ideological literature” such as the work of [Pyotr] Kropotkin or [Mikhail] Bakunin.

“We first met in 2015, when he was hanging around the university with his friends”, this source recalls. “We had interests in common – in computer technology, and sport – and became friends. There was a small circle there [in Omsk] of people who were anti-authoritarian: a milieu of young leftists, who shared a clear understanding: racism – no way, capitalism – no way.”

This friend of Filinkov’s said they were “not the sort who build communes and prepare revolution”: their main aim was to create horizontal cooperation, within which people could live side-by-side comfortably and help each other. This way of living was seen as an alternative to the state’s.

Aleksandra Aksenova, with whom Filinkov often discussed his time in Omsk, said: “He grew up in conditions of great social injustice. He also saw people’s attitudes to him, due to the fact he was a citizen of another country [Kazakhstan]. How could he not become an anti-fascist?”

Viktor himself has said that in 2016, because of the views he held, he was several times attacked by nationalists.

Both Aksenova and Filinkov’s friend from Omsk said that Viktor had come to know Aleksei Poltavets, who would later confess to the murder of an associate of the “Network” defendants in Penza. Of the other future defendants Viktor knew little, but he had heard their names, says the source in Omsk.

“It wasn’t so much about going to demonstrations or getting together in groups”, Filinkov’s Omsk friend said. “It was that we tried to live by the principles of anti-authoritarianism, anarchism, anti-fascism. And of course we spent time together: cycling, skating, playing around with Linux, trying to write [computer] programmes, listening to music, hanging out, climbing on roofs.”

Police detain a demonstrator outside the courthouse in Petersburg where Filinkov and Boyarshinov were sentenced on June 22, 2020. Photo by David Frenkel, Mediazona

Police detain a demonstrator outside the courthouse in Petersburg where Filinkov and Boyarshinov were sentenced on June 22, 2020. Photo by David Frenkel, Mediazona

Viktor met his future wife in the summer of 2015 at an anti-fascist concert in Moscow. Aleksandra then lived in Moscow, Filinkov was just visiting. They kept in touch on line, then began talking on the phone and in mid 2016 decided to meet in Penza, midway between Omsk and St Petersburg, where Aleksandra then lived.

Aleksandra had by then got to know many anti-fascists and anarchists, including future defendants in the “network” case: she was friends with Dmitry Pchelintsev, knew Arman Sagynbaev, Igor Shishkin, Andrei Chernov and Yuli Boyarshinov, and had communicated with Ilya Shakursky. Filinkov himself said that, even by the time of the court case, he had only known some of the other defendants indirectly, or met them just once.

“My comrades got to know Vitya”, Aksenova remembers. “They grew pretty fond of him, because he knew so much about so many things. They would endlessly come to see him. ‘Vitek, help with this, help with that, my computer is broken, I need to find something, how can this be done safely?’ And he would sit and explain everything.”

Aksenova says that Filinkov grew to like Dmitry Pchelintsev, the shooting instructor and anti-fascist, who the FSB would later name as the founder of the “network” terrorist organisation. “It’s no secret to anybody that one of most well-read guys in Penza was Dmitry Pchelintsev”, Aksenova says. “He could explain his reasoning, sometimes very romanticised and sometimes loudly, but it was always interesting to talk with him.”

In court, Filinkov’s lawyer, Vitaly Cherkasov, insisted that in Penza Viktor hardly spent time with any of the others, since he was “so enchanted with his lover”.

In September 2016, Filinkov found work at a Petersburg start-up. He and Aleksandra began to live together, and then got married – partly so that Viktor could become a Russian citizen.

At the same time, Filinkov got to know Sagynbaev, and began to attend lectures on first aid. In 2017 Aksenova applied for permission to acquire a firearm: the couple then kept it in a safe in their flat.

In the same year Filinkov, along with other anti-fascists, began to visit a flat at Bogatyrsky Prospekt 22. Aksenova says: “These were meetings of friends. They discussed community projects, and how they could cooperate with each other. As was stated in court, they talked about, among other things, sociological methods of study, and how to develop a culture of discussion.”

When, at the end of 2017, Pchelintsev and other activists in Penza disappeared, Filinkov and Aleksandra tried to find out what had happened to them. Aksenova decided to travel to Kiev, and in January 2018, when it became known that the Petersburg anti-fascist Yuli Boyarshinov had been arrested, Viktor decided to fly out to join her.

Filinkov had a ticket for a Kiev flight two days after Boyarshinov was detained. He told his wife that he was leaving for the airport, but never made it to the Ukrainian capital. Aleksandra searched for her husband for two days. Later on it became clear that he had been detained by FSB officers. Filinkov said that in those days the officers tortured him with an electric shocker, in order to obtain a confession.

Filinkov and Boyarshinov at a court hearing in 2018

Filinkov and Boyarshinov at a court hearing in 2018

Filinkov spent two-and-a-half years in an Investigative Detention Centre (SIZO). During that time he reported injuries he had sustained as a result of the torture. He was diagnosed with a ruptured spinal disc, and prescribed medicine for psychological problems that he suffered.

According to the FSB, Viktor Filinkov, together with other members of the “Network”, in 2016-18 acquired firearms and learned how to use them, and “acquired the practical means to seize a building”, with the aim of making violent change to the constitutional order. The FSB claimed that the group, in which Filinkov allegedly took part, aimed at the “armed overthrow of the state power”. In the prosecution case, Viktor was named as the signals operative.

The prosecutors argued that Filinkov spoke about being tortured in order to discredit Russia’s law enforcement agencies. As evidence, they adduced the fact that Viktor did not officially inform anyone about the torture before he met with Vitaly Cherkasov, his lawyer, on 26 January [2018]. Cherkasov asserts that his client was in a state of shock, and says that he himself saw the marks [on Filinkov] that resulted from him being beaten.

Members of the Public Monitoring Commission [a civic organisation empowered to monitor conditions in places of detention] also confirmed that there were signs of torture. But no independent medical examination was conducted. Viktor’s mother met with him only several months after his arrest: according to her, it was cold and her son wore a coat: all she saw was a scar on his chin.

When the court hearings began in Petersburg, Filinkov at practically every opportunity spoke of his innocence and rejected the prosecution’s claims. In open court he said: “All that I can say is: no, it’s not true. The burden of proof lies with the prosecution. But for two-and-a-half years, the authorities have shown their bias. They have wagged their fingers at me and said that I have to prove that I am not a camel.”

Filinkov’s work colleagues said in court that he had spoken openly with several of them about his wife’s legal possession of a firearm. He had introduced her to them as “Olga” – which the FSB claimed was a conspiratorial pseudonym. The prosecution also claimed that Filinkov’s “code name” was Gena. Viktor himself insists that people started to call him by that nickname in Omsk, because sometimes he laughed “like a hyena” [“giyena” in Russian].

Public defender Jenya Kulakova (left) photographs Network Case defendants Viktor Filinkov (center) and Yuli Boyarshinov. Courtesy of Jenya Kulakova

Public defender Jenya Kulakova (left) photographs Network Case defendants Viktor Filinkov (center) and Yuli Boyarshinov. Courtesy of Jenya Kulakova

People who know Viktor well have told Bumaga that they understand why he refused to confess, which theoretically could have reduced his sentence. (According to Vitaly Cherkasov, after arrest Filinkov was offered a three-year term [if he confessed].)

“That’s just his character. He won’t confess to something that he didn’t do”, Viktor’s mother Natalia said. “I know what he is thinking: if a person is right, why should he incriminate himself? Knowing him, I wouldn’t even dare to ask if he would think about making a deal. I couldn’t have brought myself to say it to him. Just impossible.”

Aleksandra explains her husband’s decision in terms of the “prisoner’s dilemma” in game theory. There is a choice for two sides: betray each other, or cooperate. Betrayal brings greater gains for each side, and for this reason it is assumed that rational players will choose betrayal. But if both sides turn traitor, the total winnings will be less than if they cooperate.

“When all the defendants in a fabricated trial refuse to admit their guilt, and insist on what they see as the truth, then the mathematical chance that they will all be given the maximum sentence is reduced”, Aleksandra says. “In such a case there’s a possibility that the whole case will just collapse. Because everyone will say what really happened. But in our case, things were complicated because there were only three defendants in Petersburg.”

Officially, the other Petersburg “network” defendants – Igor Shishkin and Yuli Boyarshinov – made no statements that they had been tortured. But after they were first detained, members of the Public Monitoring Commission learned that Shishkin had been diagnosed with a large number of bruises and instances of localised internal bleeding, and that the bone around his eye [the lower orbital wall] had been broken. Boyarshinov stated that FSB officers came to see him in the detention centre, and that other detainees had threatened to rape him.

In his final statement to the court, Filinkov said that he understood both Yuli Boyarshinov, who had confessed to his guilt, and Igor Shishkin, who had cooperated with the investigation (and already in 2019 been sentenced to three-and-a-half years). Viktor considers that they saw no other way out.

Aksenova concludes: “He is an idealist. An idealist who sees the need to take his place in history, who takes upon himself responsibility for the big picture.

“If there were no such idealists, then we would never have an example to follow, of how a person should act in such circumstances. Maybe it will seem to some people that Viktor’s words and actions were rash, and doomed to fail from the outset. I would not argue. But these words and actions are a necessity, for us to stand up for our ideals.” 3 July 2020.

■ Please visit the Rupression web site, to see how you can support the “Network” case prisoners.

■ For more coverage of Filinkov and Boyarshinov’s trial, and of the case, see The Russian Reader, Open Democracy Russia, and Freedom News. People & Nature has written about the case too, e.g. here, and about international solidarity events.

Thanks to People & Nature for permission to reprint this article. \\ TRR

Azat Miftakhov. Photo: Victoria Odissonova/Novaya Gazeta

Azat Miftakhov. Photo: Victoria Odissonova/Novaya Gazeta Penza Network defendants during the reading of the verdict. Photo: Victoria Odissonova/Novaya Gazeta

Penza Network defendants during the reading of the verdict. Photo: Victoria Odissonova/Novaya Gazeta

Viktor Filinkov and Yuli Boyarshinov. Photo: David Frenkel/Mediazona

Viktor Filinkov and Yuli Boyarshinov. Photo: David Frenkel/Mediazona

Photo courtesy of Sota.Vision and Novaya Gazeta

Photo courtesy of Sota.Vision and Novaya Gazeta Dmitry Pchelintsev. Photo by Alexei Obukhov. Courtesy of Novaya Gazeta

Dmitry Pchelintsev. Photo by Alexei Obukhov. Courtesy of Novaya Gazeta The Penza Network Case defendants during the trial. Photo by Alexei Obukhov. Courtesy of Novaya Gazeta

The Penza Network Case defendants during the trial. Photo by Alexei Obukhov. Courtesy of Novaya Gazeta The defendants communicate with their relatives. Photo by Alexei Obukhov. Courtesy of Novaya Gazeta

The defendants communicate with their relatives. Photo by Alexei Obukhov. Courtesy of Novaya Gazeta

Viktor Filinkov at work. Photo courtesy of Rupression

Viktor Filinkov at work. Photo courtesy of Rupression Viktor Filinkov (third from left) with schoolmates in Kazakhstan. Photo courtesy of Mediazona

Viktor Filinkov (third from left) with schoolmates in Kazakhstan. Photo courtesy of Mediazona Viktor Filinkov in happier times. Photo courtesy of Rupression

Viktor Filinkov in happier times. Photo courtesy of Rupression Police detain a demonstrator outside the courthouse in Petersburg where Filinkov and Boyarshinov were sentenced on June 22, 2020. Photo by David Frenkel, Mediazona

Police detain a demonstrator outside the courthouse in Petersburg where Filinkov and Boyarshinov were sentenced on June 22, 2020. Photo by David Frenkel, Mediazona Filinkov and Boyarshinov at a court hearing in 2018

Filinkov and Boyarshinov at a court hearing in 2018 Public defender Jenya Kulakova (left) photographs Network Case defendants Viktor Filinkov (center) and Yuli Boyarshinov. Courtesy of Jenya Kulakova

Public defender Jenya Kulakova (left) photographs Network Case defendants Viktor Filinkov (center) and Yuli Boyarshinov. Courtesy of Jenya Kulakova

A scene from the courtroom in Petersburg: Yuli Boyarshinov’s lawyers are in the foreground.

A scene from the courtroom in Petersburg: Yuli Boyarshinov’s lawyers are in the foreground.

Defendant Yuli Boyarshinov’s closing statement was so short that artist Anna Tereshkina didn’t have time to finish her sketch.

Defendant Yuli Boyarshinov’s closing statement was so short that artist Anna Tereshkina didn’t have time to finish her sketch.

Viktor Filinkov’s defense team: Yevgenia Kulakov and Vitaly Cherkasov

Viktor Filinkov’s defense team: Yevgenia Kulakov and Vitaly Cherkasov “Stay human”

“Stay human” The Network defendants in the courtroom in Penza. Photo by Yevgeny Malyshev. Courtesy of 7X7

The Network defendants in the courtroom in Penza. Photo by Yevgeny Malyshev. Courtesy of 7X7